Exercitation ullamco laboris nis aliquip sed conseqrure dolorn repreh deris ptate velit ecepteur duis.

Exercitation ullamco laboris nis aliquip sed conseqrure dolorn repreh deris ptate velit ecepteur duis.

Analysis

Analysis

In 2023, the AfCFTA Secretariat announced that the Council of Ministers had made a historical move by banning AfCFTA second-hand textiles trade.

Numerous news pieces attributed to the AfCFTA Secretary-General as a justification that

[t]he decision of the Council of Ministers is a strong message that our single market will not be used as a dumping ground for used clothes coming from outside Africa.

This statement may have several interpretations. But—the attribution issue set aside—preferential trade agreements do not prevent trade and are not open to non-participating countries. Therefore, the statement seems wobbly.

Something more profound is behind the misconception, suggesting a concerning issue beyond hastily written and self-praising announcements.

The negotiations for the AfCFTA have been ongoing for years, with the textiles and apparel sector being the source of most tensions, diverse economic interests, and political stakes.

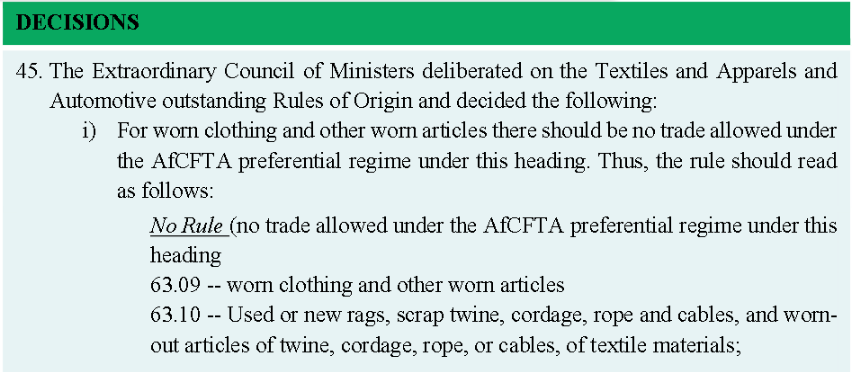

Among the many textile items under discussion, the AfCFTA Council of Ministers agreed not to allow worn clothing—as well as rags and scraps—to receive preferential treatment under the AfCFTA.

Illustration 1: Council’s decision on worn clothing items

The arguments are mainly twofold:

Allowing second-hand clothing items to enter the market competes with new clothing items. However, the industry is labour-intensive. Success stories across the continent have shown that clothing and apparel can be big contributors to job creation. For this reason, banning preferential second-hand trade is expected to stimulate production; and,

Imported second-hand clothing has a significant environmental impact where proper product end-of-life management is lacking. In several countries, discarded clothing items are dumped in open landfills, generating human and environmental health hazards. For this reason, limiting the source of such hazardous waste is expected to reduce its ecological footprint.

If the policy intent is good, the fine print makes it questionable.

The customs language assigns numeric codes to goods. These codes determine the tariff to be applied to the goods. Under trade agreements like AfCFTA, goods that meet certain requirements can be classified as tariff-free.

However, rules and guidelines exist to assign goods to a specific code.

But being pre-owned is not one of them.

In the case of the decision, the goods targeted by the alleged ban are those classified under code 63.09 and code 63.10.

Because code 63.10 is not about clothing items, let us leave this one aside and focus on 63.09.

To be classified under 63.09, goods need to meet several cumulative criteria:

Be of either clothing, blankets or rugs, home linen or other furnishing items, or footwear or headgear; and

Show “appreciable wear”: and

Be presented in large packings.

Illustration 2: HS chapter notes for made-up textiles goods

The classification provides additional information to help classify those goods as follows:

Illustration 3: Explanatory notes for the classification of worn clothing items

So what does that mean?

The classification of worn articles – and the ban from preferential trade associated with it – only apply to clothing items that show appreciable wear and are presented to the border in bulk.

Is it enough to say the agreement banned second-hand clothing? Most likely not.

It is known that bundles of clothing are delivered to informal markets. However, these bundles contain reclaimed items in good enough condition to be resold, inexpensive new clothing items, and eventually discarded retail items.

Before diving deeper, let us remind ourselves what the AfCFTA seeks to achieve.

The general objectives of the AfCFTA are to: […] e. promote and attain sustainable and inclusive socio-economic development, gender equality and structural transformation of the State Parties; […] g. promote industrial development through diversification and regional value chain development, agricultural development and food security

Article 3 of the AfCFTA Agreement

To achieve these aspirations, there may be situations where compromises are necessary.

AfCFTA second-hand textiles trade has been a contentious policy issue for a long time.

Some countries and regional communities have attempted to regulate or ban the import of used clothing due to economic, environmental, or health reasons.

In 2015, Zimbabwe introduced an import restriction in an attempt to boost its struggling textiles manufacturing industry.

However, 8 years later, the restrictive regime has not benefitted the manufacturing sector. Worse,

the country ha[s] lost over 90% of its textile manufacturers since 2015 with most of the shoe manufacturers also having left the country.

Melody Chikono, Reporter

In Zimbabwe’s case, several explanations can be advanced:

The second-hand clothing market satisfies a demand that the industry fails to meet. In a country where the average income is around 4000 US dollars per year,1 affordability is a critical purchase factor. Estimates are that 84% of Zimbabweans buy clothes in these second-hand clothing markets.

Informal cross-border trade drives the second-hand clothing market. As the article states, the COVID-19 crisis—and related border closures—has been a catalyst for the informal supply and sometimes smuggling of cheap, new items replacing traditional second-hand items.

The formal trade policies are already very stringent. For instance, the country has one of the most prohibitive average rates for goods classified under HS 63.09—167%, over 4.5 times higher than the African average. It also has one of the lowest import records for intra-African import of goods under HS 63.09.2 Yet, the manufacturing industry still suffers.

Other countries in the East African Community have also taken that path for similar reasons and with varying degrees of success.

Research suggests that the difficulties in matching domestic supply and demand could be due to the import of cheap clothing and the political economy of entrepot trade.3

Second-hand textile trade allows people to find affordable clothing and constitutes a source of income for many Africans. Where manufacturers see their market base eroded by more efficient global competitors and the widespread consumption of textile products sourced on the informal markets, the second-hand clothing trade seems to benefit first of all the informal circuits—in a context where over 80% of the labour opportunities are in the informal economy—and the same proportion finds affordable clothing from pre-owned apparel.4

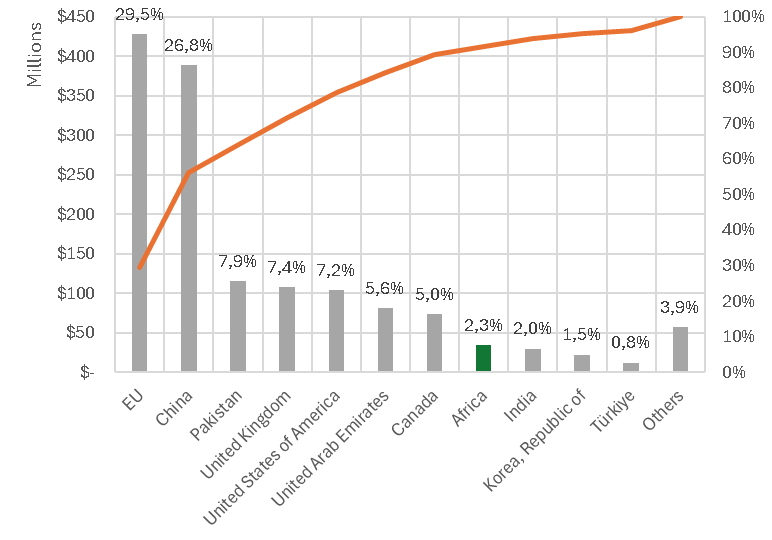

Moreover, only a small percentage of second-hand clothing imports come from other countries on the continent—if we consider the Council’s target to be second-hand clothing items.

Illustration 4: Africa’s import of worn clothes, by trading partner

Source: Calculations from TradeMap

Just the EU, China, Pakistan, the UK, the US and the UAE already represent nearly 85% of Africa’s imports of worn clothes. Intra-African trade in worn clothes, a mere 2%.

In some places, an estimated 30 to 40% need to be discarded immediately owing to their bad quality.5 However, waste management services and infrastructures may not always allow the influx of unwearable items to be absorbed, generating disastrous waste.

One of the major issues related to textile waste is that a significant portion of these discarded items are cheap, low-quality products made of synthetic fibres. Since these goods are made from petroleum, they do not biodegrade easily. Moreover, these industrial goods release toxic chemicals, notably from the dyes (as discarded natural fibre-based clothes do). However, apart from toxic chemicals, synthetic fibres also release micro- and nano-plastics, contaminating the land, water, air, and everything that lives off them.

This decision, which sounds like it has good intentions, seems to neglect that its legal implications do not specifically target second-hand clothing.

Furthermore, it signals that the AfCFTA State Parties do not embarrass themselves with the social implications or other legal obligations… Yet, the AfCFTA Agreement’s

States have the duty, individually or collectively, to ensure the exercise of the right to development.

Art. 22(2) of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights

This right to development is notably expressed as people’s “right to their economic, social and cultural development”.6

It is clear that one of the primary demands of State Parties is for the advancement of synthetic fibres to develop their textile industry. Additionally, it is estimated that clothing made from synthetic fibres will benefit the most from the AfCFTA in every segment of the value chain.

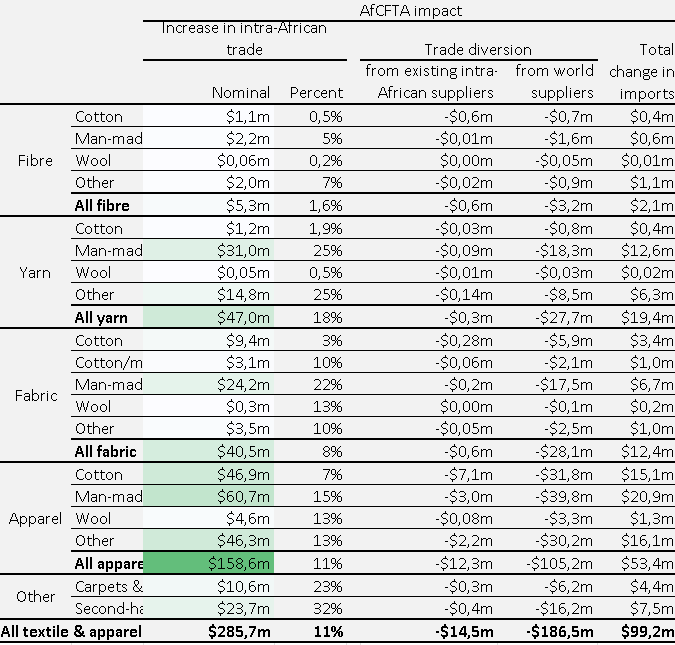

Illustration 5: Estimated impact of the AfCFTA, by value chain segment and by fibre type

Source: MacLeod (2022) Impact of the AfCFTA on Textiles and Apparel Under Different Rules of Origin Options

When it comes to the environmental argument, it thus does not seem very coherent to seek to ban one type of product while trying to produce more of it.

For these reasons, the AfCFTA second-hand textiles trade ban decision appears to be a short-sighted response to an ill-defined problem.

So what do we do with that?