Exercitation ullamco laboris nis aliquip sed conseqrure dolorn repreh deris ptate velit ecepteur duis.

Exercitation ullamco laboris nis aliquip sed conseqrure dolorn repreh deris ptate velit ecepteur duis.

Brief

Brief

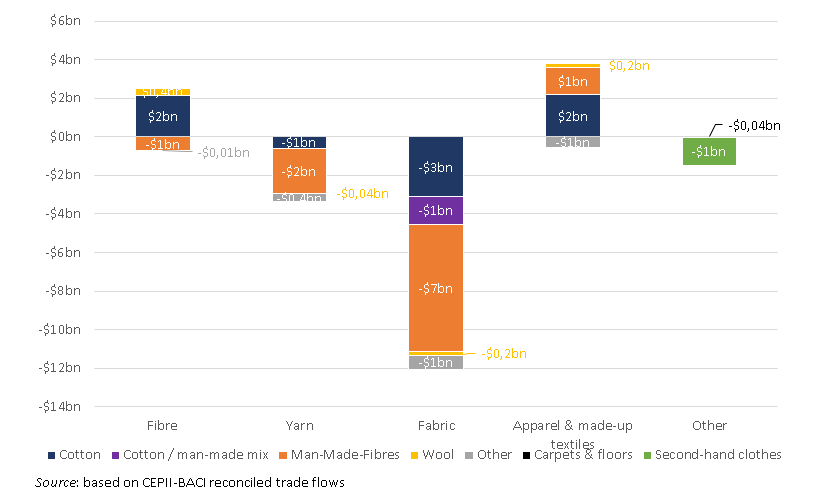

In world textile and apparel trade, finished products accounts for by far the most value of the sector. Trade in apparel and made-up textiles accounts for 65% of all of the value in the world textile and apparel market, with fabrics worth 18%, yarns worth 10% and fibres worth just 5% of world trade (other products, such as fabric flooring and second-hand clothes, account for the remaining 3% of world textile and apparel trade).

Africa outperforms at the up-stream (fibres) and down-stream (apparel) parts of the value chain, but struggles in the middle (yarn and fabric). Africa is a relatively competitive net-exporter of cotton fibres and apparel and made-up textiles, but weak in yarn and fabric production. This is similar to the industry structure of countries like Viet Nam, Cambodia and Bangladesh, which export finished goods, but rely on large volumes of imported fabrics and yarns.

This ‘missing middle’ in Africa’s textile and apparel value chain means that just 4% of Africa’s fabrics imports and 6% of Africa’s yarn imports are sourced from within the continent. Intra-African trade is strongest for apparel and made-up textiles, which account for 55% of all intra-African trade in for the textile and apparel sector.

African countries import most of their finished textiles and apparel from China. China supplies 50% of all apparel and made-up textile imports into Africa. Intra-African trade accounts for 13% of finished textile and apparel imports within the continent.

The SADC trade regime is the only one within the African continent to require double transformation rules of origin.[1] In combination with high rates of tariff protection, SADC maintains a regional apparel industry, with SADC being the African region that sources the highest share of its apparel products regionally (33 per cent, compared to 11 per cent in the EAC, 7 per cent in COMESA and 5 per cent in ECOWAS). However, the SADC regime has not substantially grown the upstream parts of the value chain, with intra-regional trade in fibres and fabrics remaining stagnant over the last 20 years.[2] The EAC, COMESA and ECOWAS regions, which employ single transformation rules of origin, have however in general also experienced growth in their internal apparel and textile trade over the last two decades.

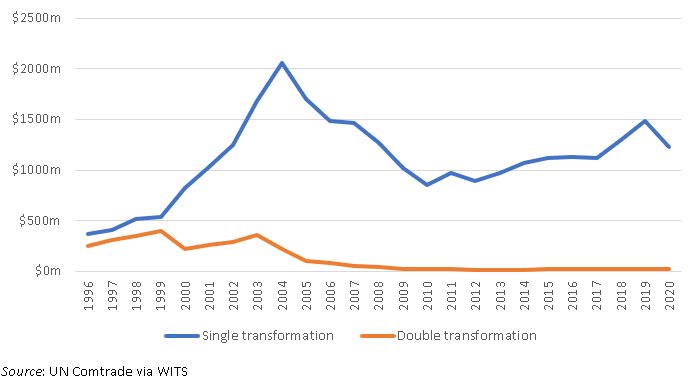

What was Africa’s experience in the EU market? African textile and apparel exports to the EU have decreased both from African exporters that benefited from single transformation rules of origin as well as those that had to rely on double transformation rules of origin. This change was driven by Africa’s declining share of the EU market for imported clothes and textiles, rather than an absolute decline in the EU market size, indicating that African exporters have in general been out-competed in the EU market even when they were afforded liberal single transformation rules of origin.

AGOA provides the best assessment of the differential impact of single and double transformation rules of origin on Africa. This is because it comprises African countries that have benefitted from single transformation rules of origin (the AGOA 3rd country fabric provision) as well as a comparable set that have been excluded from this provision and required to use double transformation rules of origin. The experience of AGOA has been growth in the absolute value and market shares of apparel exports from countries that benefited from single transformation rules of origin and the collapse of exports from countries that had to rely on double transformation rules of origin, suggesting that African countries struggle to compete when reliant on double transformation rules.

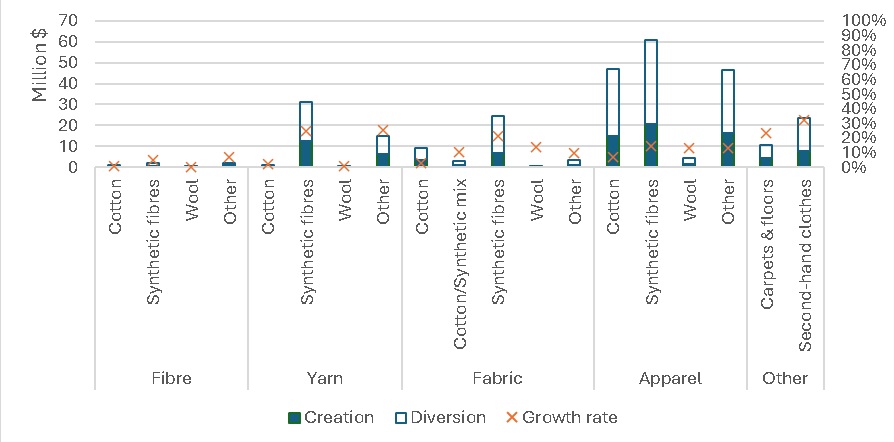

AfCFTA is estimated to have only a modest impact on intra-African textiles and apparel trade. The AfCFTA is modelled to increase intra-African imports of textile and apparel goods by $265m, resulting in total textile and apparel imports increasing by just $100m (after we net out trade diversion). This is very modest in context of Africa’s total current textile and apparel import market worth $32.9bn.

Why are the results so modest? Intra-African trade accounts for just 8 percent of total imports of textiles and apparel into African countries and the average import-weighted tariff on these imports is low with most intra-African trade in these products already flowing duty-free through pre-established REC FTAs. The AfCFTA would only liberalise intra-African trade between RECs, which is currently very limited.

Where is there most potential for the AfCFTA in the textile and apparel sector? The AfCFTA is expected to have very little impact on intra-African fibre trade (including cotton). This is because tariffs are already very low on these fibre products. The AfCFTA is also expected to have little impact on intra-African trade in yarns and fabrics, and products made from wool, because trade volumes are very low for this segment of the value chain. The AfCFTA is expected to have most potential for intra-African trade in apparel made from cotton and man-made fibres.

No African country is expected to experience more than a 10 percent increase in their total textile and apparel imports (from all sources) as a result of the AfCFTA and for most African countries, the impact is expected to be substantially less.

As many as 53 of the 75 HS headings for which RoO remain outstanding[3] in the negotiations are expected to experience increases in total imports of less than $500,000 across the entire continent.

More restrictive RoO impose greater compliance costs. Instead of being able to source inputs from the world’s most competitive suppliers, firms are restricted to sourcing from within the smaller continental market where inputs (especially yarns and fabrics) are more difficult to source, expensive, of insufficient quality, or unavailable in sufficient quantity.

RoO have been found to impose a substantial burden on intra-African trade. Business surveys conducted by ITC identify compliance with rules of origin as the main non-tariff obstacle faced in intra-African trade.[4] Restrictive rules can be especially burdensome for low-income countries.[5] The textile and apparel sector is where rules of origin can be most strict and compliance costs greatest.[6] African businesses reportedly resort to paying full tariffs despite the presence of presential trade regimes due to the high compliance costs faced in satisfying rules of origin.[7]

RoO compliance costs are estimated to amount to between 0% and 44.3% in ad valorem terms, depending on their restrictiveness. They have been estimated to amount to as much as 6.8% for NAFTA and 8% for a selection of EU trade arrangements on average for all products.[8] For ASEAN countries, the compliance costs of RoO are as low as 3.4% on average across all sectors, but are particularly restrictive in the textile and apparel sectors, exceeding 40% ad valorem equivalent cost.[9] This shows the great breadth of potential cost of complying with rules of origin relative to the most lenient change in tariff classification rules.

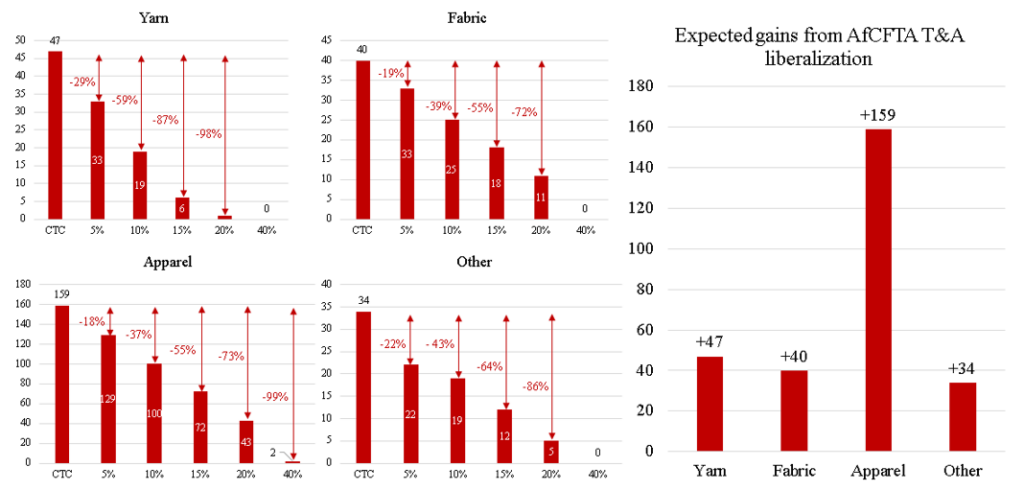

As an illustration, the most restrictive triple transformation RoO could reduce the AfCFTA’s potential to boost intra-African trade in apparel products by as much as 99%, according to simulated estimates.

The most restrictive triple transformation RoO, as an illustration, could reduce the potential of the AfCFTA to boost intra-African trade in apparel products by as much as 99%, according to The potential of the AfCFTA to boost intra-African trade in apparel products could be reduced by up to 99% with the most restrictive triple transformation RoO, according to simulated estimates.simulated estimates.

Even relatively lenient RoO, implying a compliance cost of just 5% in ad valorem terms, would potentially reduce the effect of the AfCFTA in boosting textile and apparel trade by more than a fifth, according to simulated estimates.

The compliance cost imposed by double transformation RoO could be expected to reduce the impact of the AfCFTA on the downstream apparel segment of the value chain by more than a fifth but by less than 99%.

Double transformation RoO would be particularly restrictive for the downstream apparel part of the value chain because African countries lack capacity in yarn and fabric production, meaning that producers must rely on imported yarn and fabric to remain competitive.

If all of Africa’s exports to the world of yarns and fabrics were rediverted to trade within the continent, the continent would still only be able to satisfy 20% of its demand for yarn imports and just 9% of its demand for fabrics imports. Africa is probably going to have to rely on imported yarns / fabrics for a while, even with substantial industry investments and business support. This all would suggest that double transformation rules of origin that require apparel to rely on fabrics/ yarns sourced from within the continent would be particularly constraining.

AfCFTA textile and apparel provisions are unlikely to transform the sector. An African textile and apparel strategy or work programme could cover broader necessities like industrial upgrading, branding and fashion, access to finance, market intelligence, investment, connecting with buyers, and skills training. The AfCFTA RoO can be (a modest) part of different forms of strategic directions for textile and apparel development on the continent.

[1] With a few minor exceptions at the heading level under the COMESA ad EAC’s lists of change in tariff heading.

[2] Erasmus, H., Flatters, F. and Kirk, R., 2006. Rules of origin as tools of development? Some lessons from SADC. The Origin of Goods: Rules of Origin in Regional Trade Agreements, pp.259-294.

[3] As of September 2022

[4] UNCTAD. 2021. Reaping the Potential Benefits of the African Continental Free Trade Area For Inclusive Growth. UNCTAD : Geneva.

[5] Ibid

[6] Cadot, O. and Ing, L.Y., 2016. How Restrictive are ASEAN’s RoOs?. Asian Economic Papers, 15(3), pp.115-134.

[7] Gillson, I., 2010. Deepening regional integration to eliminate the fragmented goods market in Southern Africa. World Bank Africa Trade Policy Note, (9).

[8] Cadot, O., Carrère, C., De Melo, J. and Tumurchudur, B., 2006. Product-specific rules of origin in EU and US preferential trading arrangements: an assessment. World Trade Review, 5(2), pp.199-224.

[9] Cadot, O. and Ing, L.Y., 2016. How Restrictive are ASEAN’s RoOs?. Asian Economic Papers, 15(3), pp.115-134.

Authored by

Jamie MacLeod is a Policy Fellow at the Firoz Lalji Institute for Africa. Over the last decade he has worked on trade policies and negotiations, with a particular focus on the African continent, including at the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, International Trade Centre, World Bank, and for the Ghana Ministry of Trade and Industry.